Introduction

This is a transcription of the recorded Ask TOM #SmartDB Office Hours from August 21, 2018, where Bryn Llewellyn presented an updated, narrow definition of the Smart Database Paradigm (SmartDB). It covers the time between 05:55 to 12:19. A big thank you to Bryn for taking the time to clarify the SmartDB definition.

I highly recommend watching the whole recording. Personally, however, I find it easier to browse through written documents, rather than watch videos and/or listen to audio streams. I hope you find this transcription useful, as well.

I took the liberty of adding headers for the SmartDB properties I’ve described in this post. At that time I assumed that all these five properties were mandatory, which in fact only holds true for the first two.

SmartDB Definition

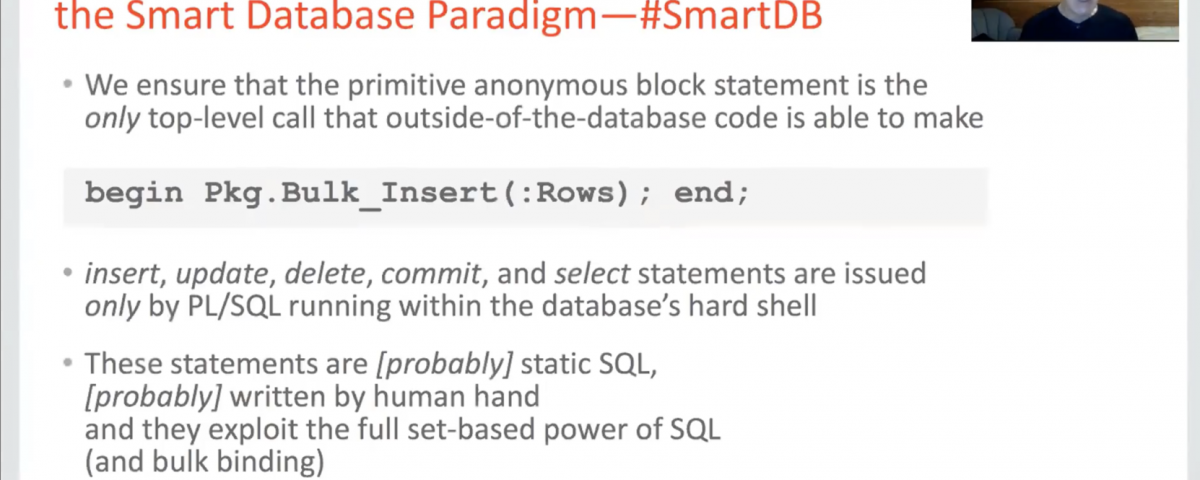

This I think is the terse and appropriate definition of our Smart Database Paradigm. And it’s as simple as this.

1. The connect user does not own database objects

By conventional regime of credentials publication – you know there is a database and there is client code that connects and it would be a miracle if anyone would set up any regime where ordinary client code connects as

sysand from that you can deduce that client code is given credentials of certain users, so that it connects and do stuff. And it’s not given credentials of other users who are considered to be more private within the database. And it’s very simple to arrange that you give credentials out to the outside world only to schemas (there is no reason that it should be only one, but it’s easier to talk as it is one) […] which are empty of objects and which when they are created have zero privileges apart from the obviouscreate session.That’s the starting point. And we won’t fuss with whatever public privileges, there’s no sensible way to talk ‘bout that and we leave that out of the picture.

2. The connect user can execute PL/SQL API units only

And then […] the user who owns that empty schema is given exactly and only execute privileges on a well-defined set of PL/SQL subprograms who have been designed to be the API of the application backend that the database hosts to the outside world. And that means by construction the only sensible thing, why I should say the only thing at all you can do (if you don’t trouble ourselves with

select * from all_usersor something silly like that) is execute these API subprograms. And they’re designed to be single operations, so it would be very funny, if you wrotebeginand thenapi.number1;,api.number2;and so on, but here is no way to stop anyone doing that. But the spirit of it is, that each time you do a top-level database call, you call just one subprogram. And indeed, it’s the case that these very straight forward procedural set of steps ensures, that the people who know the credentials you’ve given out, can only invoke your API subprograms.And that is the Smart Database Paradigm.

SmartDB Recommendations

Everything else that we say under the umbrella of it, is let’s say recommendations, icing on the cake and notions that could be useful as applications get bigger and bigger and more complex.

3. PL/SQL API units handle transactions

But you can see that a straight corollary of that statement of the paradigm is that, obviously we assume that there’s tables and someone’s gonna put stuff in and get stuff out by

select. Where those SQL gonna come from? Well, they cannot come from the outside world by construction. In other words, theinsert,update,deleteandcommitof course, andselectstatements that […] must be issued to implement the application’s purpose, they can only come out of PL/SQL code inside the database. Okay. So, if I state the paradigm as I did at first, then this bit here, let me highlight it

is not a statement of the paradigm, it’s a theorem that you could deduce from that axiom that is the paradigm. Okay.

4. SQL statements are written by human hand

And now this bit

has troubled a lot of people. It’s not […] at all a requirement that you use only static SQL, it’s just a happy fact, that the huge majority of requirements for SQL and ordinary OLTP applications are well met by PL/SQL static SQL. And that’s why I’ve put the word “probably” there. And there’s a huge advantage in using static SQL of course, because of all the rich metadata that you can get to learn various properties of the application in a heartbeat like these days in 12.2 where are the

insertshappening and what tables are involved and whatinsertsat what statement locations, right. Just by querying up the right metadata tables.And this one here

is hugely contentious. My point (and Toon’s too) is that SQL is a very natural language. It maps perfectly on to the way people talk about the information requirement in the business world. All this entity-relationship modeling stuff that maps so directly onto tables. And if you write your SQL ordinarily by human hand, well it’s not going to be that difficult in the common case, because it wraps, I should say maps so obviously to the real world that your application is modeling. That’s not to say that there’s anything in the Smart Database Paradigm that prohibits generated SQL. Not at all. And there was a huge misunderstanding about that in Twitter. Rather it means, that it’s not particularly remarkable if one writes SQL to achieve the end goal.

There’s gotta be programming involved. Some of the programming is in PL/SQL and some of it is in SQL. These two languages are a very natural fit for the task at hand, that’s all.

5. SQL statements exploit the full power of set-based SQL

And then the next bit, again you know,

it would be so so sensible and proper to exploit the full set-based power of SQL. You can get correct result if you do row-by-row slow-by-slow. But why would you do that, if you understand SQL, which you would. And if you write this stuff by hand, which you likely to find easy enough, that you wouldn’t worry doing it any other way. And the same goes about using the bulk binding constructs.

12 Comments

[…] In the meantime Bryn provided an updated, narrow definition of the Smart Database Paradigm (SmartDB). I recommend to stop reading here and instead read the next post. […]

I read the transcript. I didn’t like the typos*. Nor did I like seeing myself saying “gonna”, “gotta” and seeming to believe that there’s a verb “to setup.” But above all, I dislike the idea of capturing my extemporized speech as printed text. Rarely does any speaker use only orderly sentences—and nor is this a problem in speech. Indeed, every speaker misspeaks—far more than they’d think was possible until they hear a recording. However, the spoken locution style becomes offensive when slavishly transcribed to written text. Further, all nuances, emphases, ironies, implied parentheses and so on are lost. Of course when authoring written text, the writer uses various alternative devices to meet the same meta-communication goals. The net effect of Philipp’s transcript is therefore as different from my spoken version as chalk is from cheese. I hope never again to see such “pirate” transcripts.

And now to the substantive point: nothing I said even slightly implied that the Smart Database Paradigm allows commit or rollback outside the database. I see that I failed to stress, in this brief summary, that commit and rollback are the responsibility of the code behind the hard shell. But neither did I say anything about error handling. There was simply no time for any of that. I very much hope that we won’t see a new blog post from Philipp claiming that “the latest definition of #SmartDB” allows raw errors to escape to the client.

Now go to the recording of my Kscope18 delivery of my “Guarding your data behind a hard shell PL/SQL API – the detail” talk. Find it in the “Why use PL/SQL—the Movie” playlist here:

http://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLdtXkK5KBY56RKLbtH4-wyDvZhe7UZ1bB

Start watching at 00:36:57, and watch through to 00:40:05. But prick up your ears and concentrate hard at 00:39:03. With the caveat that this is extemporized speech and wouldn’t support transcription, it seems crystal clear to me. Philipp said that he’d watched this. I’m flabbergasted, therefore, that he could miss what I emphasized here and then ascribe to me the diametric opposite stance to the one I advocated.

‘Nuff said.

____________________________________________________________

There are typos like these:

—Philipp: step of steps, me: set of steps

—Philipp: statement to the paradigm, me: statement of the paradigm

—Philipp: assume that these tables, me: assume that there’s tables

You’re right, Bryn. I should have a) asked your permission and b) made sure that the transcriptions are free of typos before they are published. I apologize for that. Please let me know if I should remove the transcriptions from this blog. But I would prefer to correct the remaining typos, as I did with the ones you mentioned.

And you are also right that I am looking for a short and concise definition of the bare minimum of SmartDB, as this Twitter thread excerpt shows.

That was enough for me. In fact, it led to my blog posts published on July 18, 2018.

I’ve attended your related talk at #DOAG2017 and watched the KScope18 video referenced in your Youtube playlist. Listening to these presentations, it is evident that all information on the slide “In other words…” makes up the SmartDB definition. But the introductory sentence “In other words…” also implies that it is only a summary and that everything else that has been said before cannot simply be ignored. I therefore appreciated your replies on Twitter. And I considered your tweet about “the only bit that’s absolute” as the result of Twitter’s 280 characters limitation, especially since I quite well remember our long discussion at #UKOUG_TECH16. Well aware of where you see responsibility for

commitandrollback.Unfortunately, I could not attend the Ask TOM #SmartDB Office Hours on August 21, 2018. That’s why I listened to the recording shortly after it was released. And in this session, the SmartDB definition was significantly revised. It was reduced to the “axiom” with its illustration (first bullet in the slide). Everything else are recommendations. The problem is that the “theorem” (point two) cannot be deduced by the “axiom”.

The following “theorem(2)” would be correct (subset of the original theorem extended by

merge, but withoutcommit):insert,update,delete,mergeandselectare issued only by PL/SQLBy hiding tables behind a hard shell PL/SQL API, it is simply not possible to access these tables directly from client code. They are only accessible via PL/SQL.

The next “theorem(3)” would be wrong (subset of the original theorem extended by

rollback, but withoutinsert,update,delete):commitandrollbackare issued only by PL/SQLThese statements don’t need a table to be issued. Hence, hiding tables behind a hard shell PL/SQL API does not help to enforce “theorem(3)”. Every client code is given the privileges to execute these two SQL statements. There is no way to prohibit that. All they need is a connection to the database.

I understand that in the “spirit” of your SmartDB definition,

commitandrollbackare the responsibility of the PL/SQL API. But please don’t blame me, because your revised definition doesn’t make that clear.And of course, feel free to make your recommendations regarding exception handling a part of the SmartDB definition. But sorry, currently they are not.

In an application designed around SmartDB, you are corrected in stating that nothing can prevent the client from issuing commits and rollbacks. But based on the explanation of the API’s responsibility, one can easily deduce that any commit or rollback issued by a client will be impotent because the API is not leaving any pending database changes behind for the client to commit or rollback. That leaves nothing unresolved on this point, I believe.

Regarding error handling, Bryn said it wasn’t a focus of the Aug 21 2018 Office Hours session. But it was represented on the slide shown in the video recording at 23:20. It follows much the same advice offered by Steven Feuerstein on how to do error handling; by logging all details of an exception to an isolated log table (of course by an an autonomous transaction). This leads me to conclude that the API’s parameters should include any needed to return an error message/incident number for the client to present to the end user.

In this session the SmartDB paradigm is defined from 05:55 to 08:30. That’s just the first bullet point on the slide. The definition ends with sentence “And that is the Smart Database Paradigm”. From 08:30 to 08:48 you hear the introduction to the recommendations, making the distinction between definition and recommendations even clearer. And based on this definition it is simply not deducible that a

commitorrollbackis issued by PL/SQL only. And exception handling is not mentioned, hence not part of the definition.I believe we have this misunderstanding, because the inventors of SmartDB did not come up with a short and concise definition of the bare minimum of SmartDB. My expectation is, that such a definition is based on text and pictures only, without the need to watch a set of videos. The shorter the better.

Don’t get me wrong, videos are excellent medium to explain things, but from my point of view they are the wrong medium for the SmartDB definition.

Everything else (this video for other time ranges or other videos) might be useful, but they are not mandatory SmartDB properties according to this definition.

Phillip, I think at this point, you are being argumentative. Bryn has given a short and concise definition numerous times, but you seem to just not want to accept it.

Perhaps he can improve the language on the slide where he shows the anonymous block that is intended to make an API call. The first bullet should include rollback and merge along with insert, update, delete, commit and select, for completeness. But if by definition, only the API may use commit (the slide clearly states that), then it stands to reason that the API should never return with uncommitted data. And that, in turn means that rollback has no practical use outside of the API. I can’t put my finger on it, but I’m pretty certain I recall him saying somewhere that each API call should be written to be a separate database transaction. That would also be a helpful clarification on the slide.

I wish some of the other SmartDB Office Hours attendees would weigh in. Speaking for myself, I think I have a good handle on the minimum requirements needed for compliance with the SmartDB paradigm.

Maybe, instead of piggy-backing your PinkDB definition onto his SmartDB definition in an attempt to extend and relax it, you should write a short and concise PinkDB definition that stands on its own. Leave SmartDB out of it, since you have so many issues with it. That way, any confusion projected into your definition by the uncertain points you have in SmartDB will be eliminated. And you may find that it will take more than a brief written statement to convey your definition. You may need to give some presentations and make some videos.

I don’t agree. However, it is good to see that there are people who support SmartDB to get the best out of the database.

This is a very interesting discussion. But it’s well nigh impossible to conduct it usefully without talking ordinarily and in person. I’m therefore very much looking forward to the upcoming DOAG conference where Philipp, Toon and I will be able to do this. However—lest anyone get the opposite idea—I don’t want our discussions to be recorded and then transcribed. Rather, my aim is to leave these discussions better able to formulate what I later say and write under the SmartDB umbrella.

By the way, I don’t like the term that we’re using. I’d’ve preferred something that captured the spirit of “hard shell”, as I used it in the title of the talk I’ve referred to a few times. However, one esteemed colleague has already told me that he hates “hard shell”—just as others told me, equally forcefully, that they hated “thick”. The term we’ve ended up with was foisted on me. But we’re stuck with it now.

As of now, this seems to be the key issue:

Can we provide a precise definition of SmartDB—so precise, indeed, that one could mechanically analyze a database and determine, unequivocally, the boolean property “satisfies the SmartDB definition”? Or should we regard SmartDB as no more than a label for a set of recommended practices, where the benefit that each brings is carefully explained, and leave it at that?

Either way, it’s obvious that I need to improve how I explain myself in this space. I take Philipp’s point about my use of the terms “axiom” and “theorem”. I chose this technique because it seemed to be a straightforward metaphor to capture the relationship between “basic definition of practice” and “consequences that flow from this”. Maybe I should abandon that notion. Maybe I need to revise my use of “insert, update, and delete” too. Sometimes I say “insert, update, and delete—and merge, too, of course”. But that’s a lot of syllables. I can’t say “DML” because, though many people use it for only for these kinds of SQL statement, the Oracle Database SQL Language Reference book defines it with this list:

select, insert, update, delete, merge, lock table, call, and (yes really) explain plan

Notice that this list leaves out the anonymous PL/SQL block statement and that the call statement invokes a single PL/SQL procedure—with the strange quirk that this invocation method, in contrast to the anonymous PL/SQL block, swallows the “no data found” error. And then notice that a PL/SQL procedure can do any SQL you please as long as the current user has the right privileges. I can’t point out all of this any time that I say anything about SmartDB.

I’m, therefore, starting now to think that I should simply say this:

—Give out connect credentials to people with duties that don’t include administering the database only to database users that own empty schemas and have, in addition to the unavoidable public role, only Create Session and Execute on a designed set of PL/SQL units.

Then I should say “you can deduce the consequences of this”—and leave that deduction to the reader, listener, or viewer.

It’s true that commit and rollback need special mention. Notice that these are not the only transaction control statements. The Oracle Database SQL Language Reference book defines the class with this list:

commit, rollback, savepoint, set transaction, set constraint

I like this way of formulating the goal with respect to transaction control:

—Ensure that no transaction control statement issued by client-side code can have any semantic effect.

I’m working on a new idea to support this. What If I recommend that an API jacket subprogram (as I’ve defined the term) must use pragma Autonomous_Transaction in its own declare section and that the very first executable statement is rollback? That would meet my goal because if, during the top level call that started with the jacket, you did any change-making DML, then if you don’t commit or rollback explicitly, and the top-level call to the server doesn’t end with an error other than ORA-06519, then you will anyway get that error:

ORA-06519: active autonomous transaction detected and rolled back

Notice that, for example, the still-reigning effect of set transaction read only when the call ends causes ORA-06519 unless you’ve done your own commit or rollback.

I’m thinking aloud here. Maybe I should simply recommend that each API jacket subprogram must use pragma Autonomous_Transaction in its own declare section and that the very first executable statement must be rollback. Then the consequences simply emerge, and I don’t need to say any more, except maybe to give some examples.

You can see where all this is leading. I’m thinking about the kind of separation of concerns that is made for a computer language by writing a so-called Language Reference Manual and separately a so-called User Guide.

That’s enough (you might think it’s more than enough) for now. I’ll conclude by saying that I don’t think that there’s any shame in doing my thinking in public. This means, of course, that I’ll be seen to change what I say from time to time—and often to end up with mutual contradictions and incompleteness. I’m grateful for all the criticism I’ve received to date. And I’ll look forward to the further criticism that I’m bound to get as I develop my ideas further.

Interesting. Thank you, Bryn. I’m looking forward to discussing these topics in more detail in Nuremberg.

I like the idea of making the jacket subprogram (“Pkg.Bulk_Insert” in the slide) a little smarter. I’m also thinking out loud here. I’m unclear on the purpose of issuing a rollback at the start of an autonomous transaction. There is nothing to rollback. And it leaves a pending transaction silently pending.

In any case, SmartDB should require making sure an API is smart enough to not commit something unknowingly handed to it. In our current application, I caught ourselves making human mistakes of committing data that wasn’t part of the transaction (while doing other things in other SQL Developer windows). But I also didn’t want to issue a rollback without giving it due consideration. What I decided to do is have the API (if it might change the database) explicitly start a transaction. If it succeeds, things may proceed safely. If it fails, the error is logged and re-raised, passing it back to the caller to handle.

I’d welcome feedback on this alternate idea. Maybe Bryn’s idea that leaves a pending transaction as-is is more flexible. I’d still like to know the intent of that initial rollback.

To me the “SmartDB” and “Hard-Shell” paradigms are two separate ideas that are being conflated.

I considered the definitions here part of the “Hard Shell” paradigm rather than the “SmartDB”. These definitions just seem to be changing the interface or representation of the data in the database from relations to be operated on by SQL statements, to procedural modules. Although there may be intimations from doing this, they are not logical deductions from these statements.

I considered a “SmartDB” to be one that fully implemented a data model within the DBMS; where a data model meets the definition specified in Codd’s paper Data Models in Database Management:

So that any business rule that could be implemented within the DBMS as an integrity constraint, either declaratively as an SQL constraint or assertion or programmatically using triggers would be.

This, I thought, was also the basis of Toon’s Helsinki Declaration which stated that data logic should be moved into the DBMS; and his and Lex’s book “Applied Mathematics for Database Professionals” which showed a method to implement this.

I could stop at this point safe in the knowledge that no-one could unwittingly compromise the integrity of the data within the database.

Or the “Smart DB” could be extended by implementing a “Hard Shell” to address other requirements, such as performance, where as much additional business logic as possible is implemented within stored procedures in the DBMS.

So, in summary:

A “SmartDB” is one in which a data model is fully implemented within the DBMS using declarative or programmatic integrity constraints.

A “Hard Shell” is one in which as much business logic as possible in implemented within stored procedures, and calling stored procedures is the only access outside-of-the-database code can make.

These are interesting thoughts. Thanks for sharing.